On the first night of the Yule season, something changes in the house among the lava fields.

It is not loud at first. A door creaks. Boots shake off snow. Someone laughs too early, then stops. Grýla does not turn around, but she knows. Leppalúði sets his tool down and listens.

The boys have begun to arrive.

In Iceland, the Yule Lads come one at a time, one each night for thirteen nights. By the time the first four have shown their faces, the cupboards need watching and the sheep are restless. Shoes appear in windows across the country, waiting quietly to see what the morning brings.

Let me tell you about the first four.

Sheep-Cote Clod

Stekkjarstaur (STEK-yur-stare)

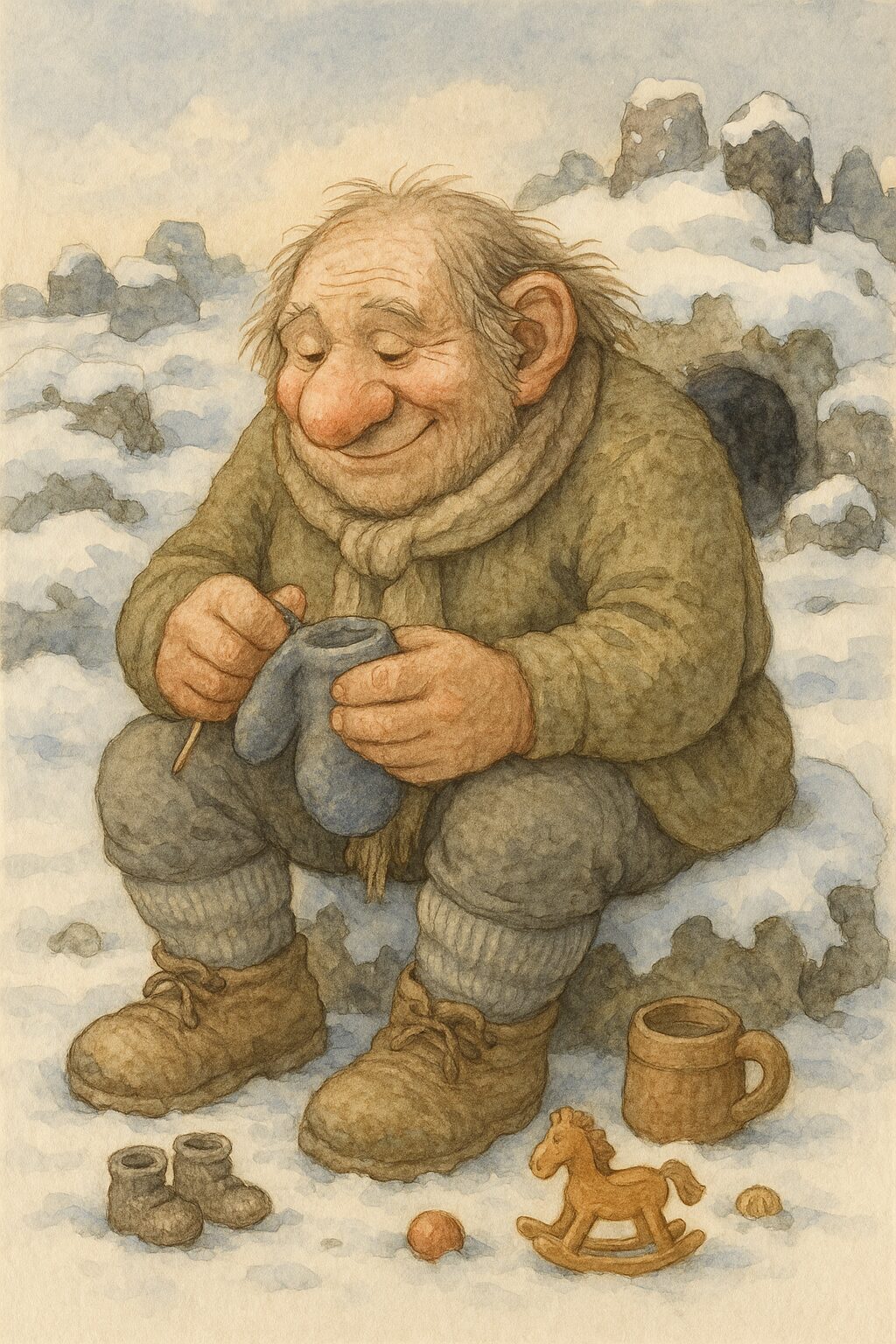

The eldest comes down from the hills stiffly, as if the cold has settled into his knees and stayed. He walks as though bending were something he once knew how to do and has since forgotten.

Sheep-Cote Clod has always had trouble with fences. Gates frustrate him. Hinges offend him. He knows the rules about enclosures, but he also knows how tempting it is to lean too far over them, to test whether wood and wire really mean what they say. He wanders near the sheep pens, peering in, convinced he can manage things better than the gate was designed to do.

Most nights, he does more bumping than helping.

The sheep scatter. The fence does not.

By morning, something is bent. Grýla notices it right away. She always does. She says nothing at breakfast. Later, Leppalúði fixes the damage around their own mountain home, tightening what loosened and straightening what bent. Elsewhere, farmers and their children do the same.

Have you ever wanted to help, but made things harder instead?

Sheep-Cote Clod watches from the doorway. He does not offer to help, but does not leave either. He pretends not to be paying attention, but he is.

He is slowly learning that wanting to help is not the same as remembering how things are meant to work.

That lesson takes him many winters.

Gully Gawk

Giljagaur (GIL-yuh-gowr)

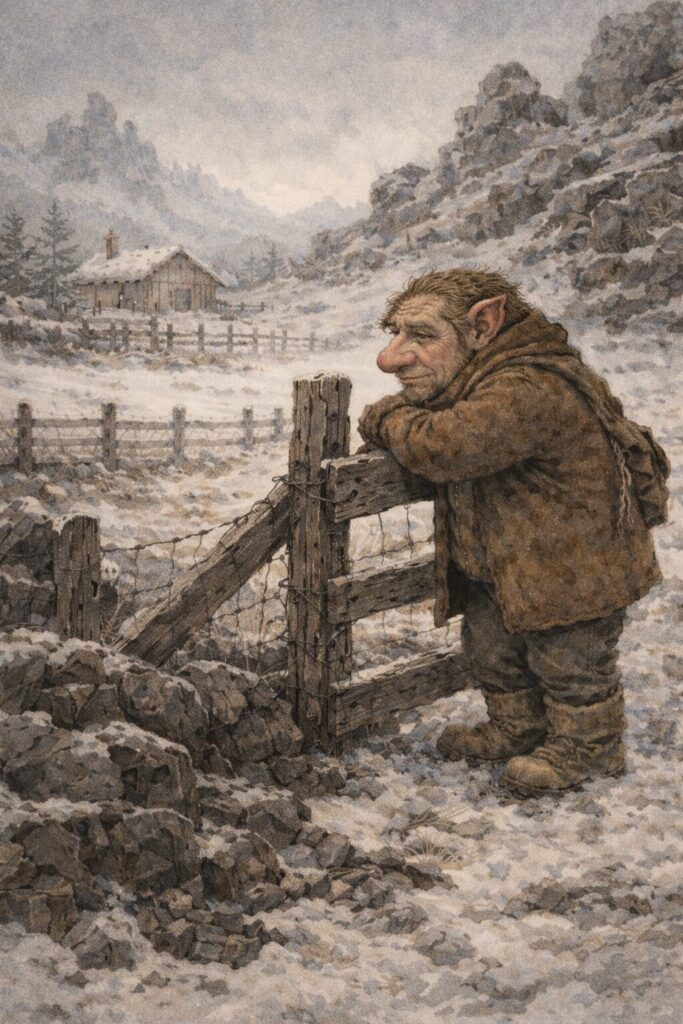

The second brother prefers places where no one expects him to be.

Gully Gawk lingers in gullies and narrow paths where snow drifts quietly and footsteps echo longer than they should. He slips into the spaces between places and stands still for long stretches of time. People forget he is there. This works to his advantage.

He listens more than he moves.

He follows the sound of milk. Streams, buckets, barns. When a cup goes missing, he is often nearby, close enough to hear the question being asked, studying the stream.

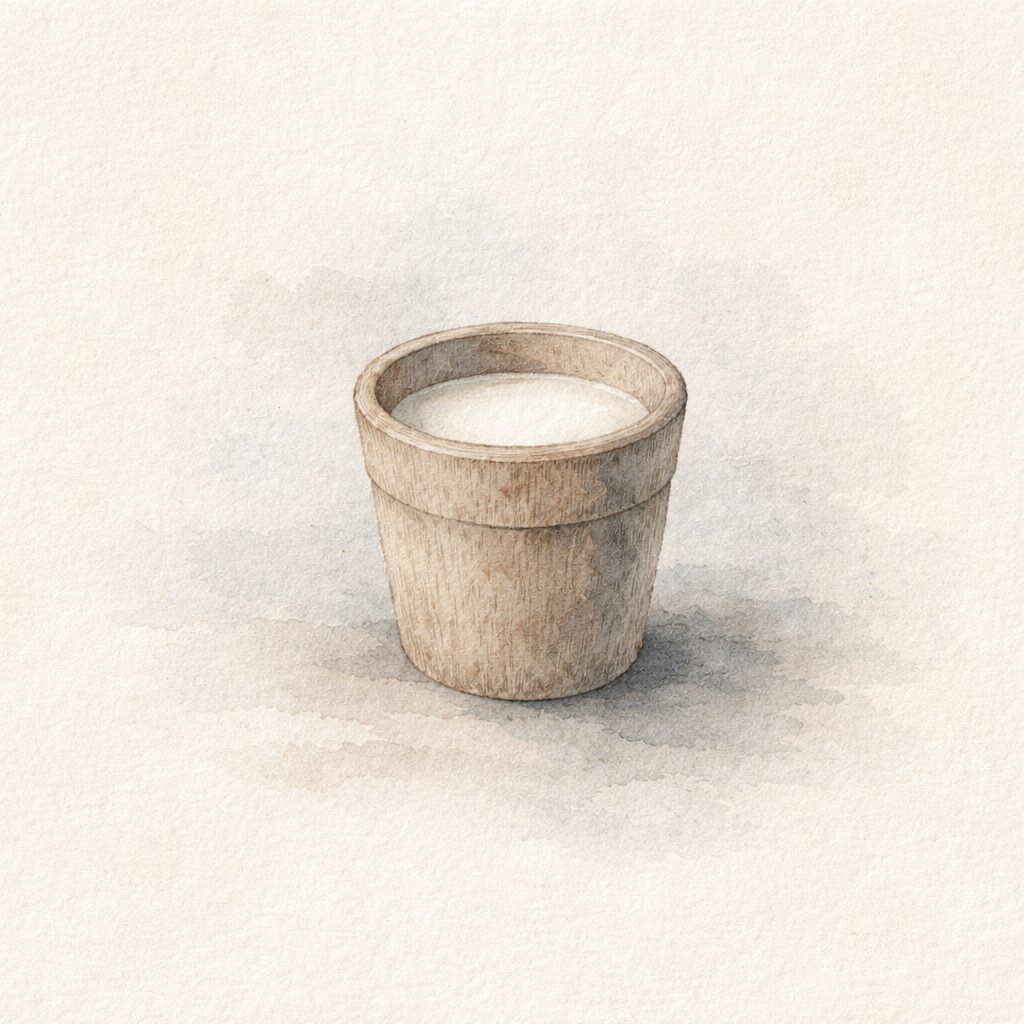

No one calls him out directly. Grýla keeps track in her own way. She notices patterns. Leppalúði sets one cup farther back than the rest, not hidden, just out of easy reach. Sometimes he sets an extra cup aside.

Gully Gawk notices. He always notices. Who in your family notices when something small has changed?

By nightfall, everyone has learned to count the cups before bed.

Stubby

Stúfur (STOO-fur)

The third brother is the shortest, quick on his feet, and never quite convinced there is enough to go around.

Stubby hates waste. Scraps bother him. Half-finished things bother him most of all. Pots, pans, and crusts draw him like a magnet, especially when he thinks no one is paying attention. He waits for the moment everyone looks elsewhere, after people scrape plates clean and set meals aside.

He scrapes pans so thoroughly they shine. Sometimes he scrapes food meant for tomorrow.

That does not go unnoticed.

Grýla corrects him without raising her voice. Often, a look is enough. Have you ever gotten a look that said everything without a word? Leppalúði makes sure they share the next meal slowly, leaving nothing unattended or rushed. He leaves a little extra for everyone, spread evenly across the table.

Stubby eats less than he wants and more than he needs.

He is learning a lesson many young adults learn slowly. Just because something is almost finished does not mean it belongs to you. He learns to wait.

He does not like it.

Spoon-Licker

Þvörusleikir (THVUR-uh-slay-kur)

The fourth brother has a different kind of patience.

Spoon-Licker waits near the hearth. He lingers where steam rises and people set down pots, watching hands instead of faces. Spoon-Licker listens for the scrape of wood against iron. He is not bold, he is careful.

When someone leaves a wooden spoon unattended, he quietly takes it, licks it clean, and returns it polished.

It is hard to be angry with him. The spoon comes back polished, as if he were doing the household a favor. Grýla lifts an eyebrow when she finds it hanging where it belongs. Leppalúði turns it over once, then hangs it higher.

Spoon-Licker looks up. He notices where it rests now. He files that away for later.

He is learning about timing. About asking. About the thin line between cleverness and courtesy.

Have you ever done something clever, then realized later you should have asked first? Spoon-Licker is not there yet.

By the time these four arrive, the house feels different. Louder. More crowded. More watchful.

Outside, children place shoes in windows and go to sleep thinking about what they might find. Sometimes there is a small gift. Sometimes a potato. Neither arrives by accident.

The Yule Lads are not cruel. It is that they are young, and push where they should pause. They learn, slowly, what it means to live in a household where everyone notices.

Above the house, snow keeps falling. Inside, the fire stays lit.

And farther up the path, more boots are already making their way down the mountain.

More from Iceland’s Christmas Legends

- Santa’s Northern Neighbors

- Grýla: Winter Mother of the Mountains

- Leppalúði: The Quiet Troll Dad

- Jólakötturinn: The Great Yule Cat of Iceland

- The First Four Yule Lads (Current)

- The Middle Five Yule Lads

- The Last Four Yule Lads

- How Icelandic Children Celebrate with the Yule Lads

- What Santa Thinks of the Yule Trolls

- Why These Stories Matter in the Dark of Winter

If you’d like Santa to share a story or bring a little wonder to your home or event this season, my visit calendar has a few open spots. I would love to meet you.